Summary

In Kenya, the peri-urban county of Machakos was already dealing with an array of public health and environmental challenges when COVID-19 hit. The arrival of the pandemic led to a countywide health crisis and economic downturn that brought a range of new problems and exacerbated existing ones.

With responsibility for local food systems, healthcare, sanitation and pandemic containment measures, the local government found itself under huge strain. Similarly, traditional urban food markets struggled to function.

As was the case throughout Kenya – and Sub-Saharan Africa more widely – the disruptions to these markets meant poor urban communities had difficulty accessing safe and nutritious food. Moreover, those who worked in and around the markets were in economic turmoil. Income and job loss were common – not just for the vendors but also for an array of market-related small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), like produce transporters and family farms.

In response to these impacts, the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) launched an emergency initiative called Keeping Food Markets Working (KFMW). Machakos County was one of six urban locations in Africa and Asia where its ‘policy and coordination’ workstream was active.

Taking local gender sensitivities into account, this workstream consisted of vendors, market committees, county policymakers and other urban food system stakeholders working together to gather evidence about locally specific food system challenges during the pandemic. They then co-designed a series of bespoken policy options to address them.

These policy options aimed to empower market workers and enhance local policymakers’ decision-making regarding keeping urban markets working during the current crisis – and any future shocks.

This case study looks at the process and resulting policy options toolkit for Machakos County.

Note: You can access the short case study here.

Key Insights

- Good governance – and knowing your city and its food system network – is a cornerstone to resilient urban food systems

- Focus on empowering residents to shape and support a resilient urban food system

- City local governments can use existing global networks to share knowledge about sustainable urban food systems approaches (see Food Action Cities).

Context and objective

Before the pandemic, Kenya was already dogged by food insecurity and its associated public health issues. The national prevalence of moderate to severe food insecurity was almost 70% for the 2018–2020 period, an increase of 15% on the 2014–1016 period.1 In 2020, an estimated 4% of children under five years-old suffered from wasting and 20% from stunting. Anemia was prevalent in almost 30% of women of reproductive age..1To curb the spread of COVID-19, the national government ordered a comprehensive lockdown, which included travel restrictions, school closures and the sudden shutting of urban food markets. Successive waves of the virus were met with partial lockdowns, which involved nightly curfews and mandatory face mask wearing in public places, like markets. Despite these measures, COVID 19 hit Kenya hard. The capital, Nairobi, was severely impacted, with reports of high numbers of infections. At the same time, city residents experienced food supply disruptions, healthcare service constraints, diminished economic activity, loss of livelihoods and rising debt.

Lying just 60km southeast of the Kenyan capital, Machakos soon fell victim to similar trends, although the true scale of the county’s pandemic was difficult to determine. With a population of approximately 1.4 million2 and a large low-income community, the county was in the midst of rapid urbanisation.3,4 With informal settlements increasingly sprawling over its hilly landscapes, a large proportion of its residents had limited access to healthcare. Consequently, many families struggled at home without reporting cases. Around the same time, environmental disaster struck. Flooding and then drought devastated harvests of subsistence crops like maize, sorghum and beans. Swarming desert locusts in eastern Kenya caused further crop damage and loss.As a result, the local population suffered from a decrease in dietary diversity1, with communities prioritising staple foods, like cereals, over fresh fruit and vegetables.Border closures caused by the pandemic created further problems. With its semi-arid climate, Machakos typically has to source foods from nearby counties like Kiambu and Busia – as well as from across the Tanzanian border. This reliance on external food sources made it especially vulnerable to disrupted supply chains. The result was that its vulnerable communities were more likely to lose their access to safe, affordable and nutritious foods from urban traditional markets.

The action needed

Under the ‘policy and coordination’ workstream of the emergency KFMW programme, GAIN engaged in a participatory, gender-sensitive manner with local policymakers, market committees, vendors and other urban food system market stakeholders in Machakos County. The approach was to gather evidence about traditional urban food markets and the wider food system during the COVID-19 pandemic in a rapid manner. Then GAIN worked with local stakeholders to co-design a selection of tailormade practical policy options, to be presented to the local government in the form of a toolkit. All the policy options were linked to real world, evidence-based problems that had been identified and prioritised by local stakeholders. They all had the capacity to be scaled up and build long-term resilience into the local food system. Taking local government mandates, budgets and pre-existing food-nutrition policies into account, they could be implemented on their own or ‘mixed and matched’ with other policies. Providing widespread access to the policy options toolkit was critical. Consequently, GAIN undertook a communications campaign, in the form of additional workshops for key audiences.

Actions taken

In July 2020, planning for the KFMW programme began. Implementation of the policy and coordination workstream started in late September 2020. Final workshops were conducted in November 2021, when the Machakos Policy Options Toolkit became available. The objective of the Toolkit was to empower market stakeholders, enhance local government food policymaking – and, ultimately, ensure the most vulnerable local people had access to nutritious food by keeping urban food markets working.

The first step to building the Toolkit was to define the problems hindering market operations, explore their causes and prioritise the challenges. This started by mapping out each market’s stakeholders, including vendors, market committee members and local food governance personnel – as well as the food systems linked to the markets.

Food systems are made up of the people, animals, institutions, ecosystems and infrastructure that relate to food production, retail, consumption, diets, nutrition and health.5 They are shaped by external forces like globalisation, trade, politics, income distribution, population dynamics, society, culture and the environment.

The food environment is an integral part of the food system. Understanding it is key to responding to the needs and opportunities of vulnerable urban communities. It forms the link between food supply chains and household acquisition and consumption of food. As well as food producer/retailer messaging and marketing, it is concerned with food’s diversity, affordability, quality, safety and desirability.6

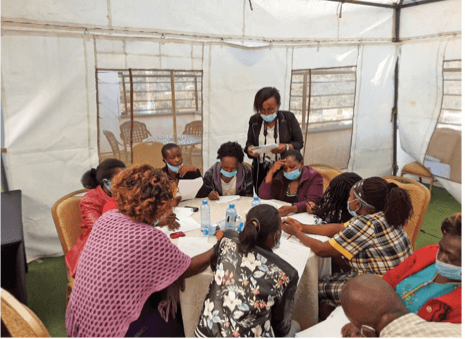

Once the mapping was completed, Rapid Needs Assessments were conducted via vendor surveys, interviews and focus groups. Two policy workshops ensued, in which local stakeholders co-designed policy options.

GAIN policy experts facilitated the workshops and shared pertinent examples of best practice from around the world. They did this through a multi-stakeholder process adapted from the Overseas Development Institute’s toolkit.7 It involved setting out a problem statement and then mapping its causes. GAIN used the results to create a unique food policy toolkit specific to Machakos.

Who is involved

This policy workstream was part of GAIN’s wider KFMW programme. As well as local Kenyan and global GAIN teams, in Machakos County it involved food market vendors, women vendor groups, market committees and SMEs linked to traditional urban food markets and county government policymakers. Some national government representatives were also involved because of their links to the county markets.

Enabling factors

An expert advisory panel, comprising of 12 members, provided guidance and support for the whole KFMW programme. At least two experts were based in each of the countries where the programme ran (Kenya, Mozambique and Pakistan). Their areas of expertise included public health, food systems, food safety, food-related SMEs and urban governance. Eighty per cent of the panel were women. Additionally, there were two GAIN co-chairs, Ann Trevenen-Jones, based in the Netherlands and Obey Nkya, based in Tanzania.

Difficulties faced

Challenges were two-fold. They either related to market stakeholders’ pandemic experiences or to practicalities around evidence-gathering and policy option co-design.

Market vendors highlighted numerous pandemic-related issues. They reported a substantial decrease in customers, an increase in supplier prices and suppliers even discontinuing deliveries altogether. Many said that their food security and nutritional health were negatively impacted.

There were numerous reports of pre-pandemic issues such as the market infrastructure lacking cool storage – as well as adequate water, sanitation and hygiene facilities. These existing challenges made the situation during the pandemic worse. Initial government support came in the form of handwashing stations, but it was said to be undermined by a lack of consistent management and water supply. Market traders described how they implemented safety measures themselves and even brought their own water supplies. They called for better government enforcement of pandemic safety measures.

Issues relating to transport were manifold. Mobility restrictions led to confusion – and reported corruption – around the legality of permits and food transportation. Customers were said to be avoiding markets because of a fear of catching COVID-19 on public transport. There were numerous tales of vendors adapting by becoming mobile and selling food closer to residential areas. Food quality, safety, loss and waste had worsened, as a result.

Many vendors raised mental health as an issue. They said their financial and mental health problems were intertwined with food supply issues, pandemic mitigation measures and the extensive use of mobile finance. In this regard, they were under financial pressure from desperate customers reversing digital transactions after buying produce.

Regarding their local government, vendors felt that Machakos County did not have the right policies in place to keep urban food markets working during the pandemic. They recognised that clearly defined food and nutrition policies and strategies existed at national level, but felt they should be devolved to local authorities.

Finally, gender inequalities were an issue that needed to be addressed. While almost two-thirds of the vendors involved were women, the few vendors who sold higher value meat and poultry were all men.When it came to evidence-gathering and policy option co-design, difficulties arose in conducting some aspects of the Rapid Needs Assessment – such as market vendor surveys, key informant interviews and focus groups – because of successive waves of COVID-19 and related restrictions. The process was also impeded by ongoing issues like the reduction of vendors in the market due to income and/or employment loss, or ill health.

Impacts to date

The result, to date, is that the Toolkit provides the Machakos County government with a raft of real-world ideas for improving local food policymaking. It outlines market stakeholders’ priorities and linked policy options in seven areas:In terms of food safety, options included the urgent establishment of waste management protocols, the introduction of food hygiene and safety training and the appointment of county government and market vendor champions. For market infrastructure, the possibilities included a rapid audit of all facilities and the creation of gender-balanced stakeholder teams to manage market operations and explore infrastructure investment opportunities, especially with regards to sanitation and cold storage. Regarding an increase in the number of informal vendors selling on the street, one of the options included the development of integrated networks of wholesale markets, retailers and vendors – linking in street vendors by formalising their status. To tackle disrupted food systems, the potential policies included the strengthening of locally sourced year-round food production – by supporting schools and other public institutions to embrace urban agriculture. Also, mobile technology could be employed to communicate about nutritious local food alternatives to unavailable produce.For urban agriculture, the options included mapping public and private spaces where food can be grown and the promotion of school, work, hospital and municipal food gardens. Potential food waste policies included the development of public procurement principles around priority purchasing from markets. In practice, this could mean local government contracts with vendors and SMEs to purchase perishable foods that cannot be sold because of curfew constraints. The food could be used in schools, hospitals and municipal canteens. When it comes to income and job loss, one solution was the creation of a public works programme in conjunction with the national government to provide short-term relief. Financial management support and debt relief could also be considered – as well as reviewing market and vendor fees for basic services, like water and sanitation.

Note

GAIN’s Keeping Food Markets Working (KFMW) programme is an emergency response to the COVID-19 crisis, providing rapid support to food system workers, to small and medium enterprises supplying nutritious foods, and to keeping fresh food markets open. To find out more about this program visit https://www.gainhealth. org/impact/our-response-covid-19

Footnotes:

- The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021 (fao.org)

- Kenyan National Bureau of Statistics. (2019). 2019 Kenyan Population and Housing Census: Volume II.

- World Bank Document

- Population living in slums (% of urban population) – Kenya | Data (worldbank.org)

- HLPE Report # 12 – Nutrition and food systems (fao.org)

- Concepts and critical perspectives for food environment research: A global framework with implications for action in low- and middle-income countries – ScienceDirect

- ODI. Toolkit, Successful Communication, A Toolkit for Researchers and Civil Society Organisations. www.odi.org/ publications/5258-problem-tree-analysis